Is Biochar “Shovel-Ready”? Unpacking Key Facts

1:3

One ton of carbon stored in biochar = 3 tons of CO2 removed from the atmosphere [source].

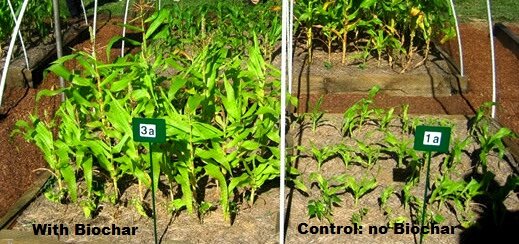

Biochar’s key environmental advantages include carbon sequestration, nutrient and water retention (reducing therefore the needs for irrigation and chemical inputs), the potential to divert streams of waste into value, reduced risk of runoff, greater flexibility of water sources (e.g., gray water or treated water), improved soil relationships, and all-around healthier plant life.

Biochar offers two-for-one carbon storage. As biochar is baked in anaerobic conditions (conditions of no oxygen) through a process called pyrolysis, it does not combust during production nor create emissions. Instead, it takes materials that may have been burned or otherwise buried and decomposed via landfill, and turns biomass into a valuable soil enhancer. This soil enhancement then facilitates healthier plant life with deeper, more robust roots, which is where carbon from the atmosphere can then go into storage.

3:1

Biochar offers an estimated 3:1 grower return on investment.

If biochar is so miraculous, then that begs the question: what does it cost? I think a better question is:

What net value does biochar create? Economic + environmental + social value.

The environmental advantages above can’t go without consideration. Speaking in economic terms, biochar costs more than alternatives such as peat-based amendments, but over time it offers at least three-fold value in financial return alone.

For golf courses, such value could be returned in the form of a 40% reduction in water usage and other inputs. This even leaves aside the possible returns of telling a better story about the sustainability of one’s golf course (and thus attracting talented job applicants and new customers).

A further reason for optimism may be that biochar remains a relatively fractured and specialty market. With advances in production methods and achieving economies of scale, the current cost of anywhere from $900 to $2500 per ton could fall into the low hundreds.

Better yet, golf courses could play a leading role in helping this market mature and achieve cost parity.

The diagram below shows what goes into the cost of biochar. Other key determinants of cost include feedstock availability and prices.

Image from Science Direct

1:9000

One gram of biochar contains about 9,000 square feet of surface area [source].

That’s nearly two basketball courts or 1.5X the average putting green at Augusta in just a gram of biochar!

How could this be? A microscopic view reveals that biochar particles have a porous structure with many openings. This structure is actually its key to sustaining microbial life. This space along with its carbon-rich content facilitates cation exchange capacity (CEC), which ultimately leads to retaining water and nutrients with greater ease (for turfgrass and superintendents).

Photo from Earth Dance Organics

29.6 million

Golf courses produce about 29.6 million tons of grass clippings every year.

Could this present a solution for circularity?

Research shows that lawns produce about 8 tons of grass clippings per acre per year. According to the GSCAA, the typical golf course maintains about 95 acres of turfgrass. With the latest count of golf courses in the world at approximately 39,000, we can roughly estimate that golf courses maintain 3.7 million acres of turfgrass globally.

That’s about 29.6 million tons of grass clippings per year.

Now, a couple of nuances apply: 1) Not all turfgrass is created equal, 2) Many courses use products to limit growth (thus saving on other critical inputs and labor), and 3) Most of the weight of grass clippings comes from water.

Nevertheless, when we start to look at all the possible sources of carbon-based biomass or feedstock for biochar, it becomes a bit more clear how its cost might decrease.

Turfgrass is just one possibility, and perhaps not the greatest despite its potential “circularity”. Biochar could even help with forest fire management via removal of deadwood (before the forest fire ever happens). Imagine getting the advantages of charred soil without the emissions and ill health effects caused by a massive forest fire!

The important thing is to consider the multitude of ways in which biochar could help not only with amending and improving soil, but also with diverting streams of waste.

It’s also important to note that biochar quality can vary widely. Not all biochars are created equal. In the case of turfgrass, different turfgrass varieties and localities may prefer char made from different feedstocks. Finding the perfect matches represents an exciting creative challenge, and one still in need of research and experimentation.

Here are some candidates for biochar feedstock:

Turfgrass clippings (and other green waste)

Deadwood from forestry management

Corn husks

Sugar cane (and other excessively-grown monocultures)

Invasive species

Food waste (though this may be better for composting)

Pretty much anything carbon-based!

Conclusions

Biochar is by no means a silver bullet, but it does hold significant untapped potential in and beyond golf. It’ll be fun in the coming years to see what role golf might play in accelerating the growth of this market. Biochar production methods vary widely (from DIY with paint cans to full-scale kilns), and its costs remain to be projected at industrial scale (basically because the demand is lacking, but golf could help fix that).

Despite the nascent nature of the market and prohibitive upfront costs, biochar still creates significant financial return even without considering the many advantages it has in turning a golf course into what North Shore Country Club Superintendent Dan Dinelli calls a “living bio-filter”.

Photo from biochar.co.nz

To make things just a little more “grounded” for golf, here’s a list (which is by no means exhaustive) of golf courses already beginning to implement biochar :

Lochiel GC

Pauanui GC

Resources for further learning: